On November 18, 2013, the Oxford Dictionaries announced on their blog that the 2013 word of the year was selfie, which they define as “a photograph that one has taken of oneself, typically one taken with a smartphone or webcam and uploaded to a social media website.”

On November 21, Erin Gloria Ryan posted a controversial piece on the popular feminist website Jezebel. In it, she claims that selfies “aren’t empowering; they’re a high tech reflection of the fucked up way society teaches women that their most important quality is their physical attractiveness.” Ryan goes on to argue that selfies just teach women to be narcissistic, and to receive validation of their narcissism by posting selfies on social media websites for “likes” or approval.

Ryan’s article sparked debate amongst feminist web circles, including a comment thread on the original article in which hundreds of women posted their own selfies as a way to refute Ryan’s claim that their motivations were purely narcissistic and were instead based in self-love and positive validation of their own bodies.

Scrolling through the images of these women, I was struck by one thing: just how many different kinds of women chose to represent themselves… young women, old women, fat women, thin women, white women, women of color, women with disabilities, butch women, femme women. In this comment thread, I saw the kinds of women who have traditionally been left out of media representations. It feels like stating the obvious to point out that traditional media representations of women have tended to favor women like Ryan, who, from her profile photo on her Jezebel article (a selfie, no less), appears to be thin, white, and feminine.

So it isn’t surprising that Ryan failed to take into account the powerful potential that selfies represent to women who aren’t like her, women who, prior to the rise of internet culture, looked to tradtional media sources to find themselves reflected and instead were met with nothing but a void, an invalidating emptiness that has always seemed to say to these women: “you do not and should not exist.”

For underrepresented women like this, selfies aren’t a symptom of the “fucked up way society teaches women that their most important quality is their physical attractiveness.” Instead, they’re a powerful tool used to challenge the ways women are taught that only certain kinds of physical attractiveness have value. When women who have traditionally been left out of media representation take photos of themselves and post them online, they’re creating spaces that radically challenge the status quo, spaces that can be deeply transforming.

I only had one friend when I was 14-years-old. Her name was Weetzie and she was a gum-chomping, bleach-blonde, punk rock, glitter-dusted pixie of a girl. I met her at a time when I most needed someone like her in my life.

At 14, on the brink of becoming an adult, of becoming a woman, I wasn’t that different from Weetzie. I was a glitter-hair-extension-wearing, Doc-Marten-stomping outcast. Growing up in the “inner-city,” where hip-hop reigned supreme, punk didn’t make you cool… it made you weird. And no one wanted to be friends with the weird girl.

So, I became friends with Weetzie, instead.

Of course, Weetzie wasn’t real. Not really. She was the titular character of Francesca Lia Block’s Weetzie Bat series, a collection of short novels written for young adults set in sparkling, glittering Los Angeles. In the series, Weetzie goes on adventures with her best friends Dirk and Duck (who are boys who love each other), falls in love with My Secret Agent Man, and they all live together in a sweet little cottage, along with their daughters Cherokee Bat and Witch Baby.

Even though Weetzie wasn’t real (not really), she represented to me a world of possibility, a world outside the norm, where girls don’t always have to conform to traditional gender roles, where there are non-traditional ways to raise a family, where traditional relationships can be redefined, where platonic relationships and romantic relationships don’t have to exclude one another. A world where girls get to be the protagonist, the creator of their own narratives instead of being relegated to being a supporting character in someone else’s.

It was the first time I was exposed to such a world. It was the first time I’d ever felt like I’d seen someone like me represented in any kind of media. And even though she wasn’t real, I loved her for it.

The Weetzie Bat series was powerful for me because it was the first time I saw myself reflected in the larger world. It was the first time I felt that my desires for something different were validated. It was the first time I’d ever read about two men being in love with each other and that being okay. It was the first time I’d ever encountered characters who were obviously people of color (characters like Coyote, a Native American man who starred in the films Weetzie’s family made; Witch Baby’s first love, Angel Juan, whose family immigrated from Mexico; and Cherokee’s first love, Raphael, who was the son of a Chinese fashion designer and a Jamaican artist).

As a woman of color who never felt like she fit any kind of stereotype, I found these encounters to be deeply transformative.

And whenever I find myself feeling like an outcast, I return to the Weetzie Bat series and find hope there.

As an adult, I’ve been able to find pieces, find the beginnings, of the world I always hoped I would live in when I was 14, clumsy, and a punk-rock kind of shy.

While the majority of media representations still favor people who fit within societal standards of heteronormativity, of whiteness, of thinness, of able-bodiedness, I’ve been grateful for the rise of the selfie because, much the same way that reading Weetzie Bat gave me hope, seeing representations of other women who are outsiders, in their own ways, makes me believe that it really is going to get better.

Thanks to the rise of social media, I don’t have to rely on Weetzie anymore. I can turn to Facebook and see photos of my friends who are challenging norms by posting photos that highlight their queerness, or their non-binary identities, or their brown-ness. I can turn to Tumblr blogs like fuckyeahhardfemme and see so many photos of young women who are creating their own versions of femininity to create something new, something different. And this gives me hope for the future… hope that more women who have existed on the margins will finally find themselves reflected on the internet, and will find the courage they need to express to live more freely and authentically.

I’m not alone in this hope.

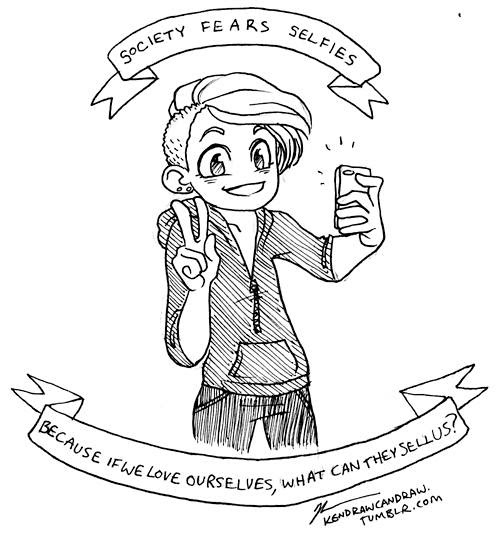

As Alicia Eler writes on Hyperallergic, “The selfie is an aesthetic with radical potential for bringing visibility to people and bodies that are othered.” This belief is echoed in many of the responses to Erin Gloria Ryan’s controversial Jezebel article, which united under the hashtags “#feministselfie” or simply “#selfie.”

Eler highlights some of these Twitter responses, such as this one from Twitter user @xoDrVenture, who wrote: “Before the internet/selfies, I legitimately didn’t know that dark skinned, natural haired black women could be beautiful.” Or, this response from Twitter user @bad_dominicana who writes: “selfies are the only place I see women like me. unlike whites, I don’t have entire industries made in my image.”

These responses highlight the important space that selfies have filled for many women, especially historically-underrepresented women. This is why selfies are so much more than narcissistic cries for help. They’re a valuable tool for marginalized women to find the representation that is sorely missing from our media, the kind of representation that allows these women to believe that they are okay, that they are not alone in the world, and that they have the right to exist on their own terms.